The section 44 juggernaut just keeps rolling. The next substantive question likely to come before the court, as a consequence of Jacqui Lambie’s disqualification on dual citizenship grounds, is whether her likely replacement, Devonport mayor, Steve Martin, is himself disqualified, for holding an “office of profit under the Crown”, with respect to his office in local government. Martin maintains that he is on solid ground, citing advice given by the then Clerk of the Senate ahead of the 2016 election.

Indeed, history suggests he has a strong case.

At least thirty percent of those elected at the first Federal elections in 1901 had experience in local government. Interestingly, one of the first disputed returns in the Federal Parliament, arising from the second election for the Commonwealth Parliament in 1903, involved an MP simultaneously holding elected office in local government, Sir Malcolm McEacharn.

McEacharn, who had been elected for the seat of Melbourne in the first Parliament, was also a councillor on Melbourne City Council, and at the time of the 1903 election, was serving as Lord Mayor. After a bitterly fought and narrowly won contest, McEacharn’s election was challenged by the losing candidate, William Maloney.

In a petition which threw everything but the kitchen sink, Maloney cited numerous irregularities in the conduct of the election, as well as the first known s.44 challenge – not on the grounds of McEarcharn’s municipal office, but that as an Honorary Consul for Japan, he held an allegiance to a foreign power.

Voiding McEacharn’s election due to polling irregularities, the High Court never addressed the s.44 question. However, given the range and breadth of the electoral petition, one assumes that if there was a possibility of a local government office being considered an “office of profit” at the time, with McEacharn’s highly visible status as Lord Mayor of a capital city – indeed, the site of Parliament – it too would have been submitted as grounds for disqualification.

In her study of the background of Members of Parliament in the Parliament from 1901-1980, Joan Rydon established that at least 20 MPs had served simultaneously in Parliament and local government during that time. Among those she named were:

- Ben Chifley (who served on Abercrombie Shire Council from 1933 to 1947, meaning, for a period from 1945, he was simultaneously Prime Minister and shire councillor),

- Arthur Calwell (who was elected to Parliament in 1940, and served on Melbourne City Council from 1939 to 1946),

- William Jack (who was mayor of Willoughby when he won the seat of North Sydney in 1949),

- Charles Adermann (who was Chairman of Kingaroy Shire Council in Queensland when he was elected to Parliament in 1943, holding both positions until 1946 when he stepped down from the council), and

- Reg Turnbull, a colourful Tasmanian politician, who served on Launceston Council (including a term as mayor) while an independent Senator during the 1960s.

Others not named by Rydon, but whose terms on council and Federal Parliament overlapped during the period of her study include Robert Katter Snr (father of the present member for Kennedy, Bob Katter) and firebrand ALP member, Eddie Ward.

Since Rydon’s study, there have been more examples of people holding municipal office while serving in Parliament, including Mark Latham (who was Mayor of Liverpool for five months after being elected in the Werriwa by-election in 1994, and only stood down from council to achieve a better life-work balance when he was diagnosed with testicular cancer), and more recently, Joanna Gash who held the NSW seat of Gilmore and was elected as Shoalhaven mayor towards the end of her term, Russell Matheson (who saw out his term on Campbelltown’s council after being elected to Parliament in 2010), and David Bradbury, who served in Parliament and on Penrith council.

Nevertheless, some parties in some states have taken the precaution of requiring holders of municipal office to resign from council before contesting a Federal election. In 1997, former Senator and Minister, Nick Minchin, told a parliamentary committee inquiring into s.44 that, as Director of the SA Liberal Party in 1993, he had advice that forced him to require prospective candidates to resign their local government office before contesting the Federal election:

the problem I had in 1993 when we received legal advice that anyone in receipt of a dollar from their position as a local councillor could potentially be caught by this section, which had not previously been thought to be the case. We had to get eight of our 12 candidates to withdraw their nominations, resign their council positions and renominate in the space of a week, spread all over South Australia. It was a nightmare of an occasion. That has been my worst experience of the potential reach of this section. Some of them were receiving literally only a few hundred dollars a year for reimbursement of expenses incurred in being a local councillor. Yet, the legal advice to those people was that that could potentially be contrary to section 44.

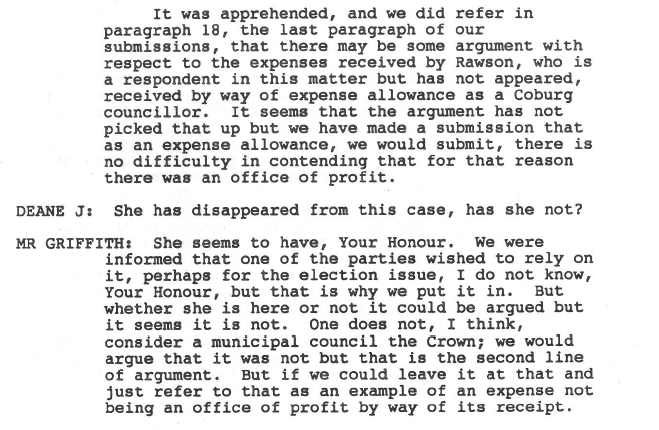

Intriguingly, the question of local government office was canvassed briefly in submissions and argument in Sykes v Cleary, the 1992 case that resulted in substantial rulings on public sector employment and dual citizenship as bases for disqualification. But it never got far out of the gate.

Ian Sykes, the petitioner, had initially challenged the status of a number of councillors who had been candidates in the Wills by-election, but these parties and/or grounds were gradually withdrawn from the proceedings. Bill Kardamitsis, the Labor candidate deemed disqualified because he had held dual citizenship at the time of the by-election, was one of the candidates serving on Coburg Council at the time, but, according to the judgment in Sykes v Cleary, had resigned from council with effect two days prior to the close of nominations.

Sykes’ petition had named an independent candidate, Geraldine Rawson, as ineligible on the grounds of her status as a councillor on Coburg council, but by the time the matter got to argument, the question regarding her had “disappeared”. Media reports at the time also indicated that another independent candidate, Katheryne Savage, was a serving councillor at the time of the election.

The Solicitor-General did refer to the question in argument, but proceeded no further other than to (apparently) put the view that while the “office of profit” limb might be satisfied even if only expenses were paid to a councillor, the limb of “under the Crown” would not likely apply to municipal office.

This view would seem to be substantially reinforced by the subsequent NSW Court of Appeal decision in Sydney City Council v Reid, a 1994 case in which the Council sought to prevent a council manager from having his appeal over an unsuccessful application for promotion heard by the public sector employment appeals tribunal.

As he fell within no other category of employee provided for in the legislation, the manager’s access to the tribunal rested on whether he could establish that he was “a person … who is employed in the service of the Crown”.

In a unanimous decision, the Court of Appeal held that he was not so employed. It appears that a subsequent effort to have the matter appealed to the High Court was unsuccessful.

In finding a local government employee was not in the service of the Crown, Kirby P found that as a statutory corporation, a local council took on a distinct identity separate from the Crown. In doing so, he relied upon the ruling of the High Court in The Mayor, Aldermen and Citizens of the City of Launceston v Hydro-electric Commission (1959) 100 CLR 654 that

Both in England and in Australia there is evidence of a strong tendency to regard a statutory corporation formed to carry on public functions as distinct from the Crown unless parliament has by express provision given it the character of a servant of the Crown.

The present Tasmanian Local Government Act establishes councils as bodies corporate, with no such express provision for it being in the service of the Crown.

Noticeably, the section dealing with immunity from liability establishes two classes with respect to those involved in local government, with the Crown being held responsible only for liabilities lying against a person appointed by the Minister or Department, as distinct from persons elected to office, or appointed or employed by a council.

341. Immunity from liability

(1) A person who is –

(a) a councillor; or

(b) a member of the Board; or

(c) the Executive Officer; or

(d) a member of the Code of Conduct Panel or an audit panel; or

(e) a member of a Board of Inquiry; or

(f) a member of a special committee or a controlling authority; or

(g) a commissioner, or an employee, of a council –

does not incur any personal liability in respect of any act done or omitted to be done by the person in good faith in the performance or exercise, or the purported performance or purported exercise, of any function or power under this or any other Act or in the administration or execution, or purported administration or purported execution, of this Act.

(2) A liability that would, but for subsection (1) , lie against a councillor, an employee of the council, or a member of a special committee, an audit panel or a controlling authority, lies against the council which established the committee, panel or authority.

(3) A liability that would, but for subsection (1) , lie against a member of the Board, the Executive Officer, a member of the Code of Conduct Panel, a member of a Board of Inquiry or a commissioner lies against the Crown.

Overall, Kirby’s view in SCC v Reid was that:

Whilst local government is indeed a form of government, it is also a creature of statute. Out of recognition of the imperatives of democratic self- government, the statutory provisions have enacted the creation of largely independent corporations accountable (in the ordinary course) not to the minister (that is, the Crown), but to the people who elect them. In this sense, the high measure of independence of statutory corporations, by which local government is ordinarily carried out, is inconsistent with viewing their employees as servants of the Crown. The exceptional powers of ministerial intervention remain that: exceptions.

In this view, Kirby was backed by his noted sparring partner of sorts, Roddy Meagher, who, while the matter centred on an employment case, opined on whether elected municipal office came within the ambit of the Crown. In an opinion entirely redolent of the Meagher oeuvre, he said:

Even the learned solicitor who argued the case for the respondent, Mr D M Bennett QC, did not advance so farouche a submission that a municipal council was the Crown, or an arm of the Crown, or an emanation of the Crown, or an agent of the Crown. The aldermen of a council are elected by popular suffrage, not appointed by the Crown. They neither ask for, nor, in general, receive, any assistance from the Crown in the discharge of their daily tasks. The extent to which the Crown can interfere with their activities is slight, and the extent to which it does is minimal.

In 2001, the majority in the Queensland Court of Appeal in Local Government Association of Qld (Inc) v State of Qld specifically held SCC v Reid as good authority for the proposition that municipal office was not a grounds for disqualification under s.44, but McMurdo P did suggest that “some analogy” could be drawn between the position of a local government councillor and the grounds in s.44.

While the “brutal literalism” of the present High Court does not indicate a predisposition to the practical consequences of a bar on elected municipal officers contesting Federal elections, the consequences are worth bearing in mind. The practical effect of requiring elected councillors to stand down from council in order to contest a Federal election, with no guarantee of winning, would be to require by-elections in those councils thus affected. Assuming the councillor-turned-candidate retains sufficient support to resume their place on council it seems an unnecessarily cumbersome and expensive exercise in local democracy.