In 1975, faced with an uncertain legal position, and mounting claims and counter-claims of breaches, the Government, acting on an Opposition proposal, made moves to establish a Royal Commission to audit MPs’ compliance with the Constitutional provisions governing disqualification from contesting elections and sitting in Parliament.

Had it proceeded, the Royal Commission would have effectively been tasked with auditing the pecuniary interests of Members of Parliament to enable references of doubtful matters to the Court of Disputed Returns. It would have been further tasked with inquiring into the “present day” appropriateness of all of the disqualifications in sections 44 and 45.

The Royal Commission was ultimately frustrated initially by the unwillingness of suitable judges to take part and then rendered unnecessary by the decision of the High Court in Re Webster in June 1975, which narrowly defined the scope of the ban on having a pecuniary interest in an agreement with the Commonwealth.

The Royal Commission proposal was set in train by a heated debate on the referral of Country Party Senator James Webster to the High Court, for consideration as to whether he was disqualified by benefiting from contracts with the Commonwealth public service. (More on the background and outcome of the case can be found here.)

During debate on the referral, the Opposition moved an amendment to initiate a judicial inquiry into section 44:

[…] the Senate is of the opinion that a judicial committee of inquiry should be appointed to inquire into and report upon-

i) the types of circumstances in which the receipt by members of the Parliament of moneys, fees and other benefits might constitute a breach of sections 44 (v) and/or 45 (lii) of the Constitution;

(ii) any other questions relating to members of the Parliament which, in the opinion of the judicial committee, as a result of its considerations under paragraph (i) above, could properly be referred to the Court of Disputed Returns; and

(iii) whether sections 44 and 45 of the Constitution are appropriate provisions in present day circumstances and conditions.’

As Senate Liberal leader Reg Withers put it in a later debate, the motive behind calling for an inquiry was that:

in no circumstances should members of the Parliament start to indulge in some sort of inquisition of member after member or senator after senator as a result of allegations made, the proper way in which to handle the matter was by way of a judicial inquiry.

With Webster’s case, the doubt over what constituted a pecuniary interest led to claims that even simple transactions with the Commonwealth, such as buying a stamp or leasing a telephone, might be caught within the definition of a pecuniary interest.

Yet as far fetched as these examples might seem, there was much genuine grist for the mill while the matter was in doubt.

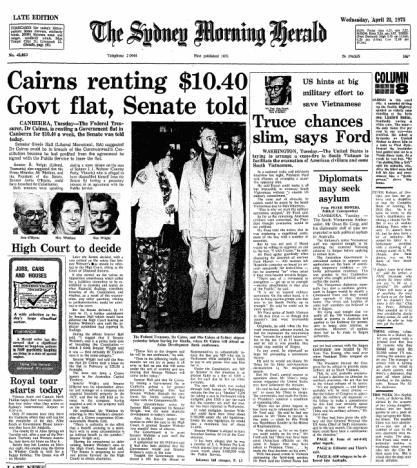

The greatest controversy was over the practice of giving some Ministers and Members of Parliament preferential access to public housing for their stays in Canberra. The most celebrated case was the then Deputy Prime Minister Jim Cairns letting a “government flat” for $10.40 a week, which was reported to be a third of the going rate for an equivalent private rental in the ACT at the time.

(Sydney Morning Herald, 23 April 1975)

But the practice was not confined to him with other Ministers including Tom Uren, Don Willesee, Moss Cass and Lance Barnard apparently having use of public housing during the period of the Whitlam Government, and former coalition ministers either renting flats under pre-existing arrangements made when in government or with the approval of the Whitlam Government.

Members of the Opposition also referred to a leasehold on Commonwealth land in the Australian Capital Territory obtained in the 1960s by the Senate President, Justin O’Byrne, on which he and a syndicate had built units.

(Before self-government for the Australian Capital Territory, administration of the leasehold system and government services, such as housing, in the ACT fell within the remit of the Commonwealth Government.)

While deploring the Opposition references to specific arrangements held by Labor members, one Labor Senator, George Georges, drew attention to the position faced by him and another MP. They had been appointed by the Minister for Aboriginal Affairs to the board of directors of a company responsible for administering public funding, so as to improve corporate governance. While specifically prohibited from receiving fees and allowances, the MPs were entitled to reimbursement of actual expenses incurred while undertaking company business. Senator Georges proposed referring his circumstances to any judicial inquiry.

Margaret Whitlam’s appointment in 1974 to the board of Commonwealth Hostels Ltd, which ran migrant hostels, and her director’s fee of $1950 a year also prompted questions from the Opposition about whether the Prime Minister thus held an indirect pecuniary interest.

Other unspecified concerns related to payments for appearing on the ABC, legal aid paid to MPs still practising as lawyers and government payments made to MPs still practising as doctors and pharmacists.

After debate, the amended motion, including the request for a judicial inquiry, was agreed to by the Senate on 22 April.

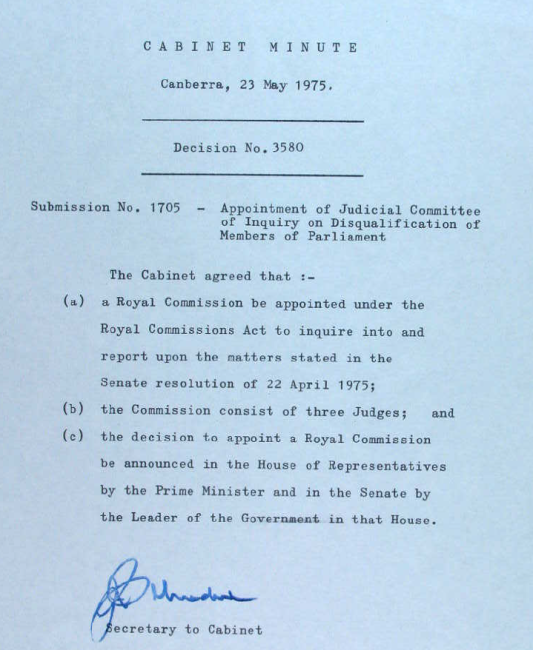

At a Cabinet meeting on 23 May 1975, the Attorney-General, Kep Enderby, proposed that the judicial inquiry be run as a Royal Commission under the Royal Commissions Act. He had consulted the Opposition who were satisfied with an inquiry led by one judge. In the end, Cabinet agreed to a Royal Commission consisting of three judges.

(From the collection of the National Archives of Australia NAA: A5915, 1705)

By the middle of June, the Government had gone so far as to approach at least one judge to take part in the inquiry. This unnamed judge, apparently of substantial repute and ostensibly acceptable to both sides of Parliament, declined to take part – indicating that he felt uncomfortable with the Webster case still underway, and a legal challenge to Jim Cairns’ flat rental by way of a “private” prosecution, launched by a common informer, in the offing. According to James McLelland, he had made known his view that the Government would be hard pressed to find any judge willing to take on the assignment while these matters were before the High Court

A month later, Sir Garfield Barwick, sitting alone, decided Webster’s case, finding that, to be disqualifying, the pecuniary interest needed to be long-standing and capable of influencing an MP in their public duties, with Webster’s dealings satisfying neither of these condition. Despite the issuing of a common informer writ, the challenge to Cairns came to nothing. (Forty-two years later, in Re Day [No. 2], the High Court would overrule Barwick’s narrow interpretation of s.44(v).) However, with Barwick’s decision guiding them, the demand for any inquiry was rendered moot, and soon the events of the Loans Affair would dominate the political scene – leading to the dismissal of the Whitlam Government five months later.

In September 1975, the Joint Committee on Pecuniary Interests made its final report. On 6 November, the Whitlam Government introduced rules for requiring a registry of interests. In December 1977, after a matter of controversy involving the Deputy Liberal leader, Phillip Lynch, Prime Minister Fraser announced that he did not consider the Joint Committee proposals sufficient, and that he proposed to establish a new inquiry, led by a judge or figure of similar standing. Federal Court justice, and former Attorney General, Nigel Bowen would lead this inquiry in 1978, making recommendations for reform. In 1984, the House of Representatives instituted a register of pecuniary interests for its members, while the Senate established a similar system in 1994.

The disqualifications in sections 44 and 45 would be the specific subject of significant Parliamentary inquiries and reports in 1981 and 1997, with recommendations for reform, but neither resulting in constitutional change.